Robert Browning

| Robert Browning | |

|---|---|

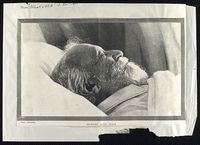

Photogravure of Robert John Browning in 1865 |

|

| Born | 7 May 1812 Camberwell, London England |

| Died | 12 December 1889 (aged 77) Venice, Italy |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Notable work(s) | The Pied Piper of Hamelin, Porphyria's Lover, The Ring and the Book, Men and Women |

|

|

|

| Signature | |

Robert Browning (7 May 1812–12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of dramatic verse, especially dramatic monologues, made him one of the foremost Victorian poets.

Contents |

Early years

Browning was born in Camberwell, a suburb of London, England, the first son of Robert and Sarah Anna Browning. His father was a well-paid clerk for the Bank of England, earning about £150 per year.[1] Browning’s paternal grandfather was a wealthy slave owner in St Kitts, West Indies, but Browning’s father was an abolitionist. Browning's father had been sent to the West Indies to work on a sugar plantation. Revolted by the slavery there, he returned to England. Browning’s mother was a musician. He had one sister, Sarianna. It is rumoured that Browning's grandmother, Margaret Tittle, was a Jamaican-born mulatto who had inherited a plantation in St Kitts. Robert's father amassed a library of around 6,000 books, many of them rare. Thus, Robert was raised in a household of significant literary resources. His mother, to whom he was very close, was a devout nonconformist as well as a talented musician. His younger sister, Sarianna, also gifted, became her brother's companion in his later years. His father encouraged his interest in literature and the arts.

By twelve, Browning had written a book of poetry which he later destroyed when no publisher could be found. After attending several private schools, he began to be educated by a tutor, having demonstrated a strong dislike for institutionalized education. Browning was a good student, and by the age of fourteen he was fluent in French, Greek, Italian and Latin. He became a great admirer of the Romantic poets, especially Shelley. Following the precedent of Shelley, Browning became an atheist and vegetarian, both of which he gave up later. At the age of sixteen, he attended University College London but left after his first year. His mother’s staunch evangelical faith prevented his studying at either Oxford University or Cambridge University, both then open only to members of the Church of England. He had substantial musical ability and composed arrangements of various songs.

Middle years

_-_Portraits_of_Elizabeth_Barrett_Browning_and_Robert_Browning.jpg)

In 1845, Browning met Elizabeth Barrett, who lived as a semi-invalid in her father's house in Wimpole Street. Gradually a significant romance developed between them, leading to their elopement on 12 September 1846. The marriage was initially secret because Elizabeth's father disapproved of marriage for any of his children. From the time of their marriage, the Brownings lived in Italy, first in Pisa, and then, within a year, finding an apartment in Florence at Casa Guidi (now a museum to their memory). Their only child, Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, nicknamed "Penini" or "Pen", was born in 1849. In these years Browning was fascinated by and learned hugely from the art and atmosphere of Italy. He would, in later life, say that 'Italy was my university'. Browning also bought a home in Asolo, in the Veneto outside Venice, and in a cruel irony he died on the day that the Town Council approved the purchase.[2] His wife died in 1861.

Browning's poetry was known to the cognoscenti from fairly early on in his life, but he remained relatively obscure as a poet till his middle age. (In the middle of the century, Tennyson was much better known). In Florence he worked on the poems that eventually comprised his two-volume Men and Women, for which he is now well known; in 1855, however, when these were published, they made little impact. It was only after his wife's death, in 1861, when he returned to England and became part of the London literary scene, that his reputation started to take off. In 1868, after five years work, he completed and published the long blank-verse poem The Ring and the Book, and finally achieved really significant recognition. Based on a convoluted murder-case from 1690s Rome, the poem is composed of twelve books, essentially ten lengthy dramatic poems narrated by the various characters in the story, showing their individual perspectives on events, bookended by an introduction and conclusion by Browning himself. Extraordinarily long even by Browning's own standards (over twenty thousand lines), The Ring and the Book was the poet's most ambitious project and has been praised as a tour de force of dramatic poetry. Published separately in four volumes from November 1868 through to February 1869, the poem was a huge success both commercially and critically, and finally brought Browning the renown he had sought and deserved for nearly forty years.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The courtship and marriage between Robert Browning and Elizabeth were carried out secretly. Six years his elder and an invalid, she could not believe that the vigorous and worldly Browning really loved her as much as he professed to, and her doubts are expressed in the Sonnets from the Portuguese, which she wrote over the next two years. Love conquered all, however, and, after a private marriage at St Marylebone Parish Church, Browning imitated his hero Shelley by spiriting his beloved off to Italy in August 1846, which became her home almost continuously until her death. Elizabeth's loyal nurse, Wilson, who witnessed the marriage at the church, accompanied the couple to Italy and became at service to them.

Mr. Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did for each of his children who married: “The Mrs. Browning of popular imagination was a sweet, innocent young woman who suffered endless cruelties at the hands of a tyrannical papa but who nonetheless had the good fortune to fall in love with a dashing and handsome poet named Robert Browning. ”[3] As Elizabeth had inherited some money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy, and their relationship together was content. The Brownings were well respected in Italy and they would be asked for autographs or stopped by people because of their celebrity. Elizabeth grew stronger, and, in 1849, at the age of 43, she gave birth to a son, Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, whom they called Pen. Their son later married but had no legitimate children. It is rumoured that the areas around Florence are peopled with his descendants.

“Several Browning critics have suggested that the poet decided that he was an 'objective poet' and then sought out a 'subjective poet' in the hope that dialogue with her would enable him to be more successful.”[4] At her husband's insistence, the second edition of Elizabeth’s Poems included her love sonnets; these increased her popularity and high critical regard so that she cemented her position as favourite Victorian poetess. Upon William Wordsworth's death in 1850, she was a serious contender to become Poet Laureate, but the position went to Tennyson.

Last years and death

In the remaining years of his life Browning travelled extensively. After a series of long poems published in the early 1870s, of which Fifine at the Fair and Red Cotton Night-Cap Country were the best-received, Browning again turned to shorter poems. The volume Pacchiarotto, and How He Worked in Distemper included an attack against Browning's critics, especially the later Poet Laureate Alfred Austin. According to some reports Browning became romantically involved with Lady Ashburton, but did not re-marry. In 1878, he returned to Italy for the first time in the seventeen years since Elizabeth's death, and returned there on several occasions. The Browning Society was formed for the appreciation of his works in 1881. In 1887, Browning produced the major work of his later years, Parleyings with Certain People of Importance In Their Day. It finally presented the poet speaking in his own voice, engaging in a series of dialogues with long-forgotten figures of literary, artistic, and philosophic history. The Victorian public was baffled by this, and Browning returned to the short, concise lyric for his last volume, Asolando (1889).

He died at his son's home Ca' Rezzonico in Venice on 12 December 1889, the same day Asolando was published. He was buried in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey; his grave now lies immediately adjacent to that of Alfred Tennyson.

The story of Browning and his wife Elizabeth was made into a play The Barretts of Wimpole Street. The play was later discovered, produced and starred actress Katharine Cornell, for whom the role of Elizabeth became a signature role. The play was a success and brought popular fame in the United States to the couple, and was eventually adapted twice into film.

Browning's poetic style

Browning’s fame today rests mainly on his dramatic monologues, in which the words not only convey setting and action but also reveal the speaker’s character. Unlike a soliloquy, the meaning in a Browning dramatic monologue is not what the speaker directly reveals but what he inadvertently "gives away" about himself in the process of rationalizing past actions, or "special-pleading" his case to a silent auditor in the poem. Rather than thinking out loud, the character composes a self-defense which the reader, as "juror," is challenged to see through. Browning chooses some of the most debased, extreme and even criminally psychotic characters, no doubt for the challenge of building a sympathetic case for a character who doesn't deserve one and to cause the reader to squirm at the temptation to acquit a character who may be a homicidal psychopath. One of his more sensational dramatic monologues is Porphyria's Lover.

Yet it is by carefully reading the far more sophisticated and cultivated rhetoric of the aristocratic and civilized Duke of My Last Duchess, perhaps the most frequently cited example of the poet's dramatic monologue form, that the attentive reader discovers the most horrific example of a mind totally mad despite its eloquence in expressing itself. The duchess, we learn, was murdered not because of infidelity, not because of a lack of gratitude for her position, and not, finally, because of the simple pleasures she took in common everyday occurrences. She is reduced to an object d'art in the Duke's collection of paintings and statues because the Duke equates his instructing her to behave like a duchess with "stooping," an action of which his megalomaniacal pride is incapable. In other monologues, such as Fra Lippo Lippi, Browning takes an ostensibly unsavory or immoral character and challenges us to discover the goodness, or life-affirming qualities, that often put the speaker's contemporaneous judges to shame. In The Ring and the Book Browning writes an epic-length poem in which he justifies the ways of God to humanity through twelve extended blank verse monologues spoken by the principals in a trial about a murder. These monologues greatly influenced many later poets, including T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, the latter singling out in his Cantos Browning's convoluted psychological poem Sordello about a frustrated 13-century troubadour, as the poem he must work to distance himself from.

Ironically, Browning’s style, which seemed modern and experimental to Victorian readers, owes much to his love of the seventeenth century poems of John Donne with their abrupt openings, colloquial phrasing and irregular rhythms. But he remains too much the prophet-poet and descendant of Percy Shelley to settle for the conceits, puns, and verbal play of the Metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century. His is a modern sensibility, all too aware of the arguments against the vulnerable position of one of his simple characters, who recites: "God's in His Heaven; All's right with the world." Browning endorses such a position because he sees an immanent deity that, far from remaining in a transcendent heaven, is indivisible from temporal process, assuring that in the fullness of theological time there is ample cause for celebrating life.

History of sound recording

At a dinner party on 7 April 1889, at the home of Browning's friend the artist Rudolf Lehmann, an Edison cylinder phonograph recording was made on a white wax cylinder by Edison's British representative, George Gouraud. In the recording, which still exists, Browning recites part of "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix" (and can be heard apologizing when he forgets the words).[5] When the recording was played in 1890 on the anniversary of his death, at a gathering of his admirers, it was said to be the first time anyone's voice "had been heard from beyond the grave."[6][7]

Complete list of works

- Pauline: A Fragment of a Confession (1833)

- Paracelsus (1835)

- Strafford (play) (1837)

- Sordello (1840)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. I: Pippa Passes (play) (1841)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. II: King Victor and King Charles (play) (1842)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. III: Dramatic Lyrics (1842)

- "Porphyria's Lover"

- "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister"

- "My Last Duchess"

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin

- "Johannes Agricola in Meditation"

- Bells and Pomegranates No. IV: The Return of the Druses (play) (1843)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. V: A Blot in the 'Scutcheon (play) (1843)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. VI: Colombe's Birthday (play) (1844)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. VII: Dramatic Romances and Lyrics (1845)

- "The Laboratory"

- "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix"

- "The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church"

- Bells and Pomegranates No. VIII: Luria and A Soul's Tragedy (plays) (1846)

- Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day (1850)

- Men and Women (1855)

- "Love Among the Ruins"

- "The Last Ride Together"

- "A Toccata of Galuppi's"

- "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came"

- "Fra Lippo Lippi"

- "Andrea Del Sarto"

- "The Patriot/ An Old Story"

- "A Grammarian's Funeral"

- "An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish, the Arab Physician"

- Dramatis Personae (1864)

- "Caliban upon Setebos"

- "Rabbi Ben Ezra"

- The Ring and the Book (1868-9)

- Balaustion's Adventure (1871)

- Prince Hohenstiel-Schwangau, Saviour of Society (1871)

- Fifine at the Fair (1872)

- Red Cotton Night-Cap Country, or, Turf and Towers (1873)

- Aristophanes' Apology (1875)

- The Inn Album (1875)

- Pacchiarotto, and How He Worked in Distemper (1876)

- The Agamemnon of Aeschylus (1877)

- La Saisiaz and The Two Poets of Croisic (1878)

- Dramatic Idylls (1879)

- Dramatic Idylls: Second Series (1880)

- Jocoseria (1883)

- Ferishtah's Fancies (1884)

- Parleyings with Certain People of Importance In Their Day (1887)

- Asolando (1889)

- Prospice

Notes

- ↑ John Maynard,Browning's Youth

- ↑ Barrett Browning Dies at Asolo, Italy; Artist, son of the Poets, Robert and Elizabeth Browning, obituary, The New York Times, 9 June 1912

- ↑ Peterson, William S. Sonnets From The Portuguese. Massachusetts: Barre Publishing, 1977.

- ↑ Pollock, Mary Sanders. Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003.

- ↑ [1] Poetry Archive, retrieved May 2, 2009

- ↑ Kreilkamp, Ivan, "Voice and the Victorian storyteller." Cambridge University Press, 2005, page 190. ISBN 0-521-85193-9, 9780521851930. Retrieved May 2, 2009

- ↑ [2]"The Author," Volume 3, January-December 1891. Boston: The Writer Publishing Company. "Personal gossip about the writers-Browning." Page 8. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

References

- Chesterton, G.K. Robert Browning (Macmillan, 1903)

- DeVane, William Clyde. A Browning handbook. 2nd. Ed. (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1955)

- Drew, Philip. The poetry of Robert Browning: A critical introduction. (Methuen, 1970)

- Finlayson, Iain. Browning: A Private Life. (HarperCollins, 2004)

- Garrett, Martin ed., Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning: Interviews and Recollections. (Macmillan, 2000)

- Garrett, Martin. Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. (British Library Writers' Lives). (British Library, 2001)

- Hudson, Gertrude Reese. Robert Browning's literary life from first work to masterpiece. (Texas, 1992)

- Karlin, Daniel. The courtship of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett. (Oxford, 1985)

- Kelley, Philip et al. (Eds.) The Brownings' correspondence. 15 vols. to date. (Wedgestone, 1984-) (Complete letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning, so far to 1849.)

- Litzinger, Boyd and Smalley, Donald (eds.) Robert Browning: the Critical Heritage. (Routledge, 1995)

- Markus, Julia. Dared and Done: the Marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning (Bloomsbury, 1995)

- Maynard, John. Browning's youth. (Harvard Univ. Press, 1977)

- Ryals, Clyde de L. The Life of Robert Browning: a Critical Biography. (Blackwell, 1993)

- Woolford, John and Karlin, Daniel. Robert Browning. (Longman, 1996)

External links

- Grave of Robert Browning

- Poems by Robert Browning

- Poems by Robert Browning at PoetryFoundation.org

- Robert Browning biography and select bibliography

- The Brownings: A Research Guide (Baylor University)

- The Browning Society

- Short Biography and Poems

- Works by Robert Browning at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Browning in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Poetry Archive: 135 poems of Robert Browning

- The Barretts of Wimpole Street at the Internet Movie Database

- A recording of Browning reciting five lines from "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix"

- Works by Robert Browning in e-book

- An analysis of "Home Thoughts, From Abroad"

- Browning Family Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin